Embracing and Embodying Cultural Humility

Committing to lifelong learning, and personal and institutional transformation.

In a previous blog about building and extending trust I introduced general humility, intellectual humility, and cultural humility as foundational to building trust. Cultural humility has profoundly impacted clinical care, public health, and community engagement around the world.1 2 Here I summarize its key principles with links to resources below.

In 1998, Melanie Tervalon and Jann Murray-García published a groundbreaking article that challenged the concept of “cultural competency” with the concept of “cultural humility.”3 4 5 Cultural humility is committing to lifelong learning, critical self-reflection, and personal and institutional transformation. Accepting cultural humility means accepting that we can never be fully culturally competent. Cultural humility is the foundation for establishing trust and respectful relationships, and for managing differences and conflict. Cultural humility means

committing to lifelong learning6 and critical self-reflection;

realizing our power, privilege, and prejudices (biases);

redressing power imbalances for respectful partnerships; and

promoting institutional accountability.

Power is the capacity or ability to direct or influence the behavior of others, the course of events, or the allocation of resources. Power comes from positional, moral, or relational authority. Authority is granted by appointment or earned by trust and credibility. Power can be exercised by embodying humility and promoting universal values,7 or by persuasion, manipulation, or deceit. The dynamics and impacts of power are multi-dimensional, context dependent, cumulative, and can be subtle. For example, the mere presence of a boss can unintentionally shut down subordinates. “Humility is to hold power in service of others.”8

Privilege is a form of unearned power that comes from social advantage. All of us have some form of privilege. Privilege exists because of sociopolitical systems and cultural norms that create, reinforce, and amplify power inequities, explicitly or implicitly. For example, in the United State, if you are like me: male, heterosexual, cisgender, or have lighter skin color, you have more privilege. We do not choose privilege (eg, being born into a wealthy family), but we can acknowledge it, and, more importantly, you can make “noble choice to forgo your status and to use your influence for the good of others before yourself” — this is general humility.9

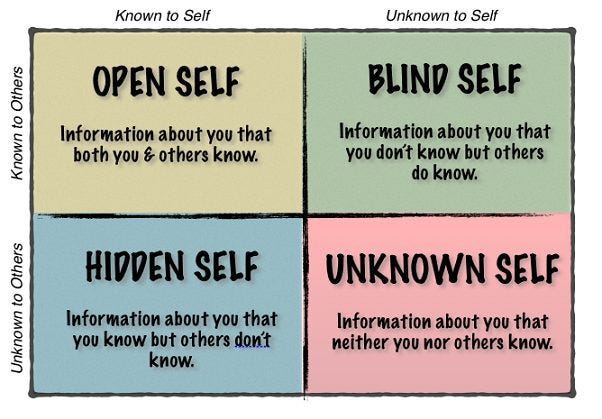

For our purposes, biases are preferences, cognitive processes, or inferences that shape our mental models, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors in ways that cause or contribute to inequities in power, privilege, opportunities, or outcomes for ourselves and/or others. Biases can be known to you and others (open self), known to you and not others (hidden self), known to others but not you (blind self), or not known to you and others (unknown self) (Figure 2).10

Implicit biases account for the unknown and blind spot biases, and are the most challenging type of bias because we all have them, and they are difficult to identify, measure, and mitigate. For example, ambiguous hiring criteria are susceptible to implicit biases. Without unambiguous, objective criteria, hiring someone you “trust” is driven, unintentionally, by implicit biases.

Our “blind self” and “hidden self” are our biggest liabilities and requires a sincere and genuine commitment — ie, willing, able, and ready — to change and grow. Seek honest and frank feedback from your fiercest critics that you trust. Even then, there is still more to uncover and learn about yourself.

Learn more about cultural humility from the following outstanding videos.

Here is 5 min video summary:

Here is the complete 30 video:

Resources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Embracing Cultural Humility and Community Engagement.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Glossary Terminology Considerations: Page 1 and Page 2.

University of Oregon. What is Cultural Humility?

Footnotes

Campinha-Bacote, Josepha. “Cultural Competemility: A Paradigm Shift in the Cultural Competence versus Cultural Humility Debate – Part I.” OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 24, no. 1 (December 4, 2018). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol24No01PPT20.

Fitzgerald, Elizabeth, and Josepha Campinha-Bacote. “An Intersectionality Approach to the Process of Cultural Competemility – Part II.” OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 24, no. 2 (April 10, 2019). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol24No02PPT202.

Tervalon, M., and J. Murray-García. “Cultural Humility versus Cultural Competence: A Critical Distinction in Defining Physician Training Outcomes in Multicultural Education.” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 9, no. 2 (May 1998): 117–25. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2010.0233.

Foronda, Cynthia, Diana-Lyn Baptiste, Maren M. Reinholdt, and Kevin Ousman. “Cultural Humility: A Concept Analysis.” Journal of Transcultural Nursing: Official Journal of the Transcultural Nursing Society 27, no. 3 (May 2016): 210–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659615592677.

Yeager, Katherine A., and Susan Bauer-Wu. “Cultural Humility: Essential Foundation for Clinical Researchers.” Applied Nursing Research: ANR 26, no. 4 (November 2013): 251–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2013.06.008.

See the “Four Stages of Competence” section Leadership is getting results in a way that inspires trust (part 2).

Universal values are values that apply to everyone, everywhere, leaving no one behind, including your adversaries. Examples of universal values include dignity, equity/fairness, compassion, and belonging. Dr. Monica Sharma, former Director of Leadership Development at the United Nations, discovered that promoting the universal values of dignity, equity, and compassion enabled field teams to tackle difficult public health problems in all corners of the world.

John Dickson (2011). WCA Summit Sunday - John Dickson - Humilitas (YouTube). This is an inspiring talk on humility.

John Dickson (2011). WCA Summit Sunday - John Dickson - Humilitas (YouTube). Th

Dr Lori Zakel. JoHari Window in Interpersonal Communication. Video lecture by Dr. Lori Zakel, Professor and Chair of the Communication Department at Sinclair College, Dayton, Ohio.