Prioritizing health programs in an era of budget cuts

Health economic concepts for priority setting and resource allocation

By the end of this blog you will understand the key concepts behind this “equation”:

A universal challenge faced by organizations with fixed budgets (eg, government agencies, managed-care health systems, community-based organizations) is “How do we set budget priorities in the face of cutbacks?” Historically, budget decision-makers follow these common practices:1

historical patterns (“last year’s budget,” organizational culture or tradition),

politics and power (authority, reaction, interests, expertise)

advocacy (``squeaky wheel gets the oil''),

needs assessments,

core services (e.g., legally mandated activities), or

equality (“every program cuts x%.”).

We can do better! The general approach is called priority-setting and resource allocation (PSRA). There is tremendous global experience in addressing the challenge of constrained or shrinking budgets in real world health systems settings.2 3

Building upon decision quality concepts, the most common PSRA framework includes:

Program budgeting and marginal analysis (PBMA),

Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA), and

Accountability for reasonableness (A4R).

While PRSA is practiced around the world, you will noticed that it is rarely used in the United States, especially now.

Program budgeting and marginal analysis (PBMA)

Program budgeting and marginal analysis (PBMA) leverages three key economic concepts:

opportunity cost,

margin, and

efficiency.

Every time we choose to use resources (people, money, time) to meet one need (say, Option A) we automatically give up the “opportunity” to use those resources to meet some other need (say, Option B). The loss benefit by not choosing Option B is the opportunity cost. In contrast to cost accounting approaches, the aim of economics is to ensure that we undertake activities where benefits outweigh opportunity cost.4

Opportunity cost is the lost benefit of the better option not chosen or not considered.

The marginal cost is the cost of producing or consuming one more unit. The marginal benefit is the gain from one more unit. Comparing these two can help determine if an additional unit is worthwhile—typically by examining whether marginal benefit exceeds marginal cost. In some contexts, economists look at the marginal benefit-cost ratio, which is marginal benefit divided by marginal cost.

In practice, we actually make changes incrementally or at the “margin”: while not changing most of our programmatic activities, we

improve a few programs,

add a few programs, and

discontinue a few programs.

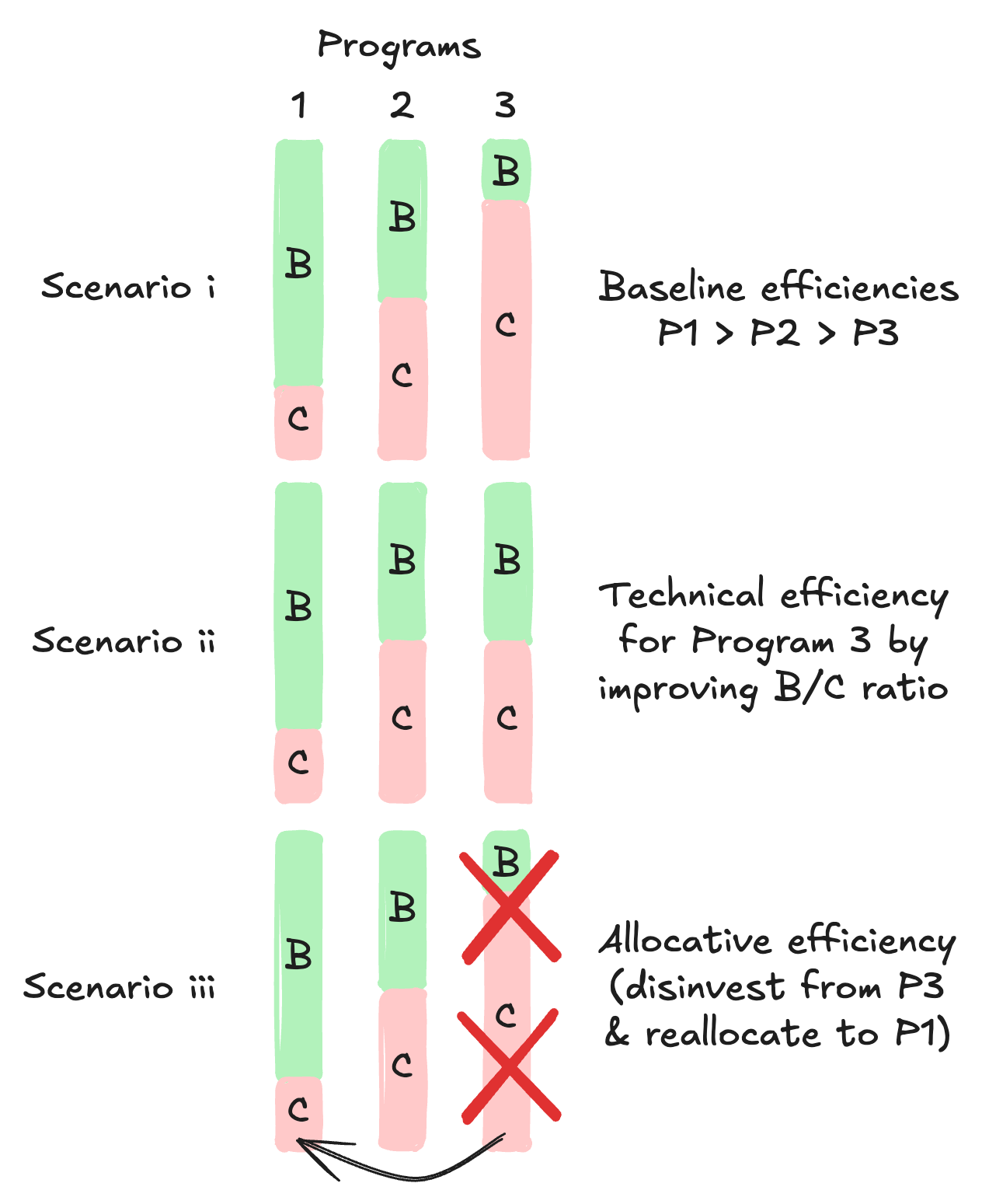

When we focus on a portfolio of programs, we have two types of efficiencies: technical efficiency and allocative efficiency. Technical efficiency is when we improve marginal efficiency by improving the B/C ratio within a program. Examples include

deploying a cost-effective intervention,

improving performance at the same cost, or

eliminating waste using lean process improvements.

Technical efficiency is when we improve marginal efficiency by improving the B/C ratio within a program.

The resources released are now available for reallocation. Allocative efficiency is when we improve marginal efficiency by reallocating resources across programs to improve organizational performance. Sometimes this includes discontinuing programs and adding new ones. Discontinuing and adding programs is a type of marginal efficiency at the organizational level.

Allocative efficiency is when we improve marginal efficiency by reallocating resources across programs to improve organizational performance.

Marginal efficiency applies to a portfolio of programs. Figure 1 depicts three programs under three scenarios: baseline, technical efficiency by improve one program, and allocative efficiency by reallocating resources from low performing to the highest performing.

PBMA focuses on both technical and allocative marginal efficiencies (Figure 1). PBMA provides health organizations a structured, deliberative process for setting programmatic and budget priorities under resource constraints, or worse, when budgets must be cut. Without a transparent, fair process for cutting budgets, organizations resort to historical practices based on power, politics, and advocacy.

For health organizations, PBMA has seven steps:5

Determine the aim and scope of the priority setting exercise: Decide whether PBMA will be used to examine changes in services within a single Department or program or between Departments/programs.

Compile a program budget: Current resources assigned to

each defined program should be identified and quantified.

Form a marginal analysis advisory panel: Key

stakeholders (managers, clinicians, consumers, etc.) should be able

to contribute to the priority setting process through this formal

Advisory Panel, or in some other clearly defined manner.

Determine locally relevant decision-making criteria:

All proposed investments or disinvestments will be assessed against

these criteria, which should reflect the mission and mandate of the

organization and the values of the community which it serves.

Identify options for service growth and resource release: (a) Service growth, (b) Resource release from gains in operational efficiency, (c) Resource release from scaling back or ceasing some services: These proposals can be developed by an organization’s senior leaders or solicited from staff through an engagement process.

Evaluate investments and disinvestments: Using the agreed-upon criteria, managers will consider options and make recommendations for moving resources from 5 (b) and 5 (c) to 5 (a) above.

Validate results and reallocate resources: The leadership group, with additional outside input as desired, will assess the allocation decisions reached through the process and make reasoned adjustments, if necessary.

Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA)

PBMA steps 3 to 6 use multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) for deliberative, structured decision making by the Advisory Panel. The Advisory Panel consists of technical and community stakeholders and differs from the Decision Board that makes final decisions. MCDA is also called multi-objective decision-making (MODM) because we want to optimize multiple objectives that have completing trade-offs.

Businesses use decision analysis to optimize one objective — profits! In contrast, health organizations get a fixed budget (general fund, grant, or managed-care capitation fees) to optimize multiple, competing objectives (improve health, eliminate wastes, etc.). Fundamental objectives are an organization’s ultimate express of their values. (See Why leaders embrace OKRs -- and you should too.)

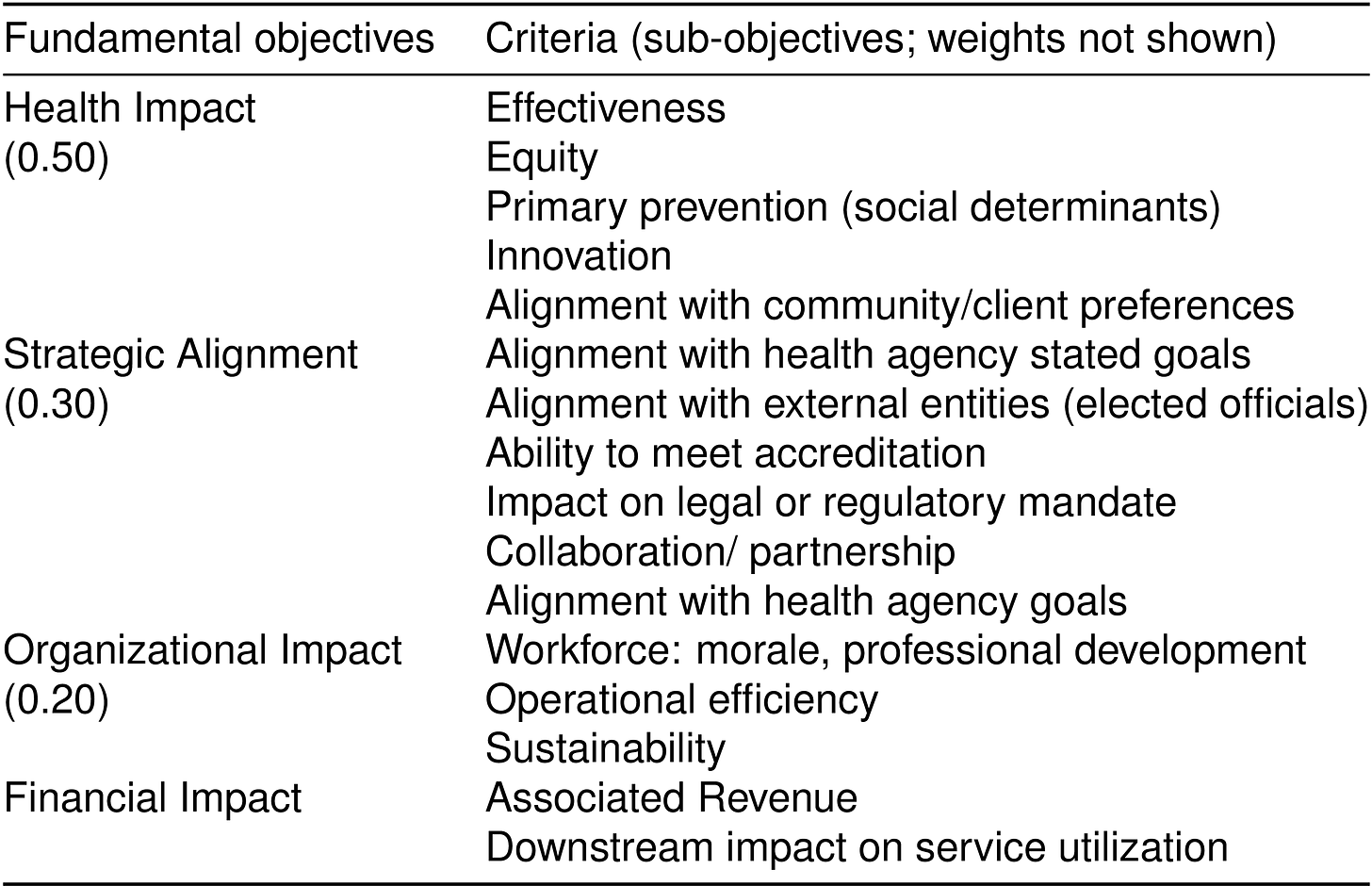

For example, in a health agency, fundamental objectives can be assigned importance weights by leadership:

health impact (HI) (0.50 weight),

strategic alignment (SA) (0.30 weight),

organizational impact (OI) (0.20 weight), and

financial impact (FI) (handled separately).

Each fundamental objective has sub-objectives (or multiple criteria) which are weighted separately (Table 1).

The Advisory Panel uses these criteria to rank programs or proposals for the purposes of investment or disinvestment (ie, budget cuts). A structured and transparent deliberative process promotes fairness and legitimacy (see Accountability for Reasonableness). These methods are applied around the world and there is growing body of literature that supports these types of structured, deliberative approaches to priority setting and resource allocation.6 7 8

Accountability for reasonableness (A4R)

Accountability for reasonableness (A4R) “serves as an important moral guide for decision makers in ensuring that their priority setting process is fair and legitimate.”9 A4R fulfills five criteria:

relevance: decisions based on reasons fair-minded people can agree are relevant under the circumstances;

publicity: reasons publicly accessible;

revision: opportunities to revisit/revise decisions andmechanism to resolve disputes;

empowerment: power differences minimized and effective participation optimized; and

enforcement: mechanisms to ensure above four conditions met.10

To earn trust you must implement A4R! Avoiding this is a big mistake!

Summary

We should be applying these concept always so that we are prepared for austere times like today.

Appendix

The MCDA can be depicted using an influence diagram that has four node types: decision, uncertainty (chance), calculation, and value (see Figure 2). Values are the ultimate and measurable fundamental objectives we aim to achieve. For clarity and simplification we will not be using uncertainty nodes. For sub-objectives (i.e., “multiple criteria”) we will use calculation nodes.

Figure 3 depicts the influence diagram for this MCDA. The Advisory Panel uses the criteria to score program proposals using a deliberate, fair, and transparent process (see A4R next section).This results in much improved prior-setting and resource allocation.

Footnotes

Craig Mitton and Cam Donaldson, Priority Setting Toolkit: A Guide to the Use of Economics in Healthcare Decision Making (London: BMJ Books, 2004), https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Priority+Setting+Toolkit%3A+Guide+to+the+Use+of+Economics+in+Healthcare+Decision+Making-p-9781405146777.

Rob Baltussen et al., “Global Developments in Priority Setting in Health,” International Journal of Health Policy and Management 6, no. 3 (March 1, 2017): 127–28, https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2017.10.

Neale Smith et al., “High Performance in Healthcare Priority Setting and Resource Allocation: A Literature- and Case Study-Based Framework in the Canadian Context,” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 162 (August 2016): 185–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.027.

Neale Smith et al., “Introducing New Priority Setting and Resource Allocation Processes in a Canadian Healthcare Organization: A Case Study Analysis Informed by Multiple Streams Theory,” International Journal of Health Policy and Management 5, no. 1 (September 24, 2015): 23–31, https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2015.169.

Neale Smith et al., “Introducing New Priority Setting and Resource Allocation Processes in a Canadian Healthcare Organization: A Case Study Analysis Informed by Multiple Streams Theory,” International Journal of Health Policy and Management 5, no. 1 (September 24, 2015): 23–31, https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2015.169.

Antonio Ahumada-Canale et al., “Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing Priority Setting and Resource Allocation Tools in Hospital Decisions: A Systematic Review,” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 322 (April 2023): 115790, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115790.

Brayan V. Seixas, François Dionne, and Craig Mitton, “Practices of Decision Making in Priority Setting and Resource Allocation: A Scoping Review and Narrative Synthesis of Existing Frameworks,” Health Economics Review 11, no. 1 (January 7, 2021): 2, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-020-00300-0.

Brayan V. Seixas et al., “Describing Practices of Priority Setting and Resource Allocation in Publicly Funded Health Care Systems of High-Income Countries,” BMC Health Services Research 21, no. 1 (January 27, 2021): 90, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06078-z.

Craig Mitton, Francois Dionne, and Cam Donaldson, “Managing Healthcare Budgets in Times of Austerity: The Role of Program Budgeting and Marginal Analysis,” Applied Health Economics and Health Policy 12, no. 2 (April 2014): 95–102, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-013-0074-5.

Lydia Kapiriri and Donya Razavi, “How Have Systematic Priority Setting Approaches Influenced Policy Making? A Synthesis of the Current Literature,” Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 121, no. 9 (September 2017): 937–46, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.07.003.

This could be a great resource for our LHJs. Would it be OK to share it through the RPHO newsletter or as a separate document?