Causal reasoning with Bayesian Algorithmic Thinking (BAT Part 2)

Transforming data into information, knowledge, and wisdom (Part 2)

Review of Part 1

In Part 1, I introduced “Bayesian networks for algorithmic thinking.” We learned that a Bayesian network (BN) is a graphical model for representing probabilistic, but not necessarily causal, relationships between variables called nodes.1 2 Nodes are just variables; eg, like field names in a data table. The nodes are connected by one-way arrows called edges. BNs have a superpower — they provide a unifying framework for understanding …

probabilistic reasoning (with Bayesian networks),

causal inference (with directed acyclic graphs), and

decision analysis (with influence diagrams).

We learned that with 2-variable causal graphs we can understand

causal/predictive reasoning, and

evidential/diagnostic reasoning.

This posting (Part 2) will cover causal/predictive reasoning.

… Bayes’ theorem

Evidential/diagnostic reasoning requires Bayes’ theorem (Figure 1). As new data/evidence becomes available, Bayes’ theorem enables us to update

probabilities (eg, risks of adverse events, diagnostic testing),

credibility of a hypothesis (eg, new evidence regarding causal claims), and

beliefs (subjective, personal beliefs).

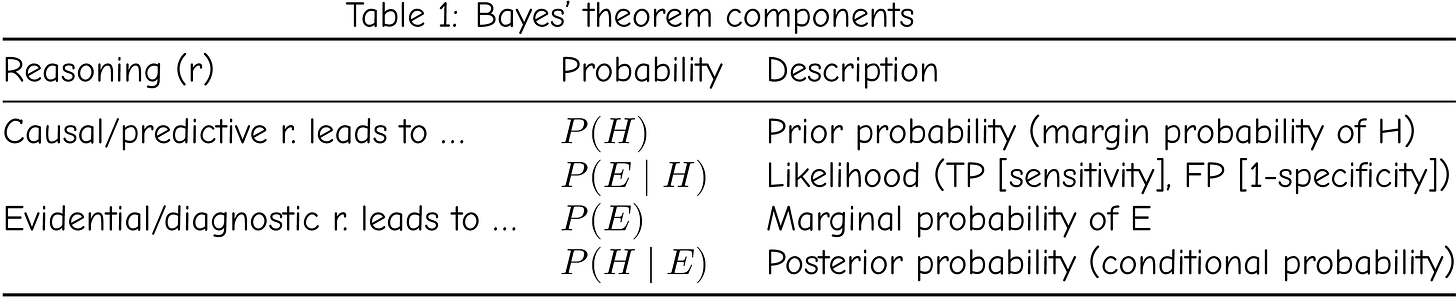

Table 1 summarizes the components of Bayes’ theorem from Figure 1.

… Aside: cause→effect vs. hypothesis→evidence nodes

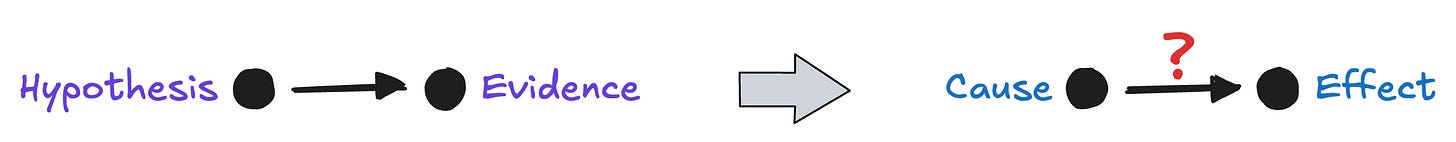

I use Cause → Effect nodes when a causal relationship is established or assumed. Otherwise, I use Hypothesis → Evidence nodes. Here is another way of thinking about it: both depictions below are acceptable, but using hypothesis-evidence nodes is preferred because you do not need to keep adding ? marks.

Cause → Effect nodes (without the ? mark) are used for predictive modeling.

Hypothesis → Evidence nodes are used for diagnostic modeling.

Bayes’ theorem applies equally to both; just pay attention to conditional probabilities; eg, P(Evidence|Hypothesis) vs. P(Hypothesis|Evidence) — rows 2 and 4 in Table 1.

… Bayesian algorithmic thinking

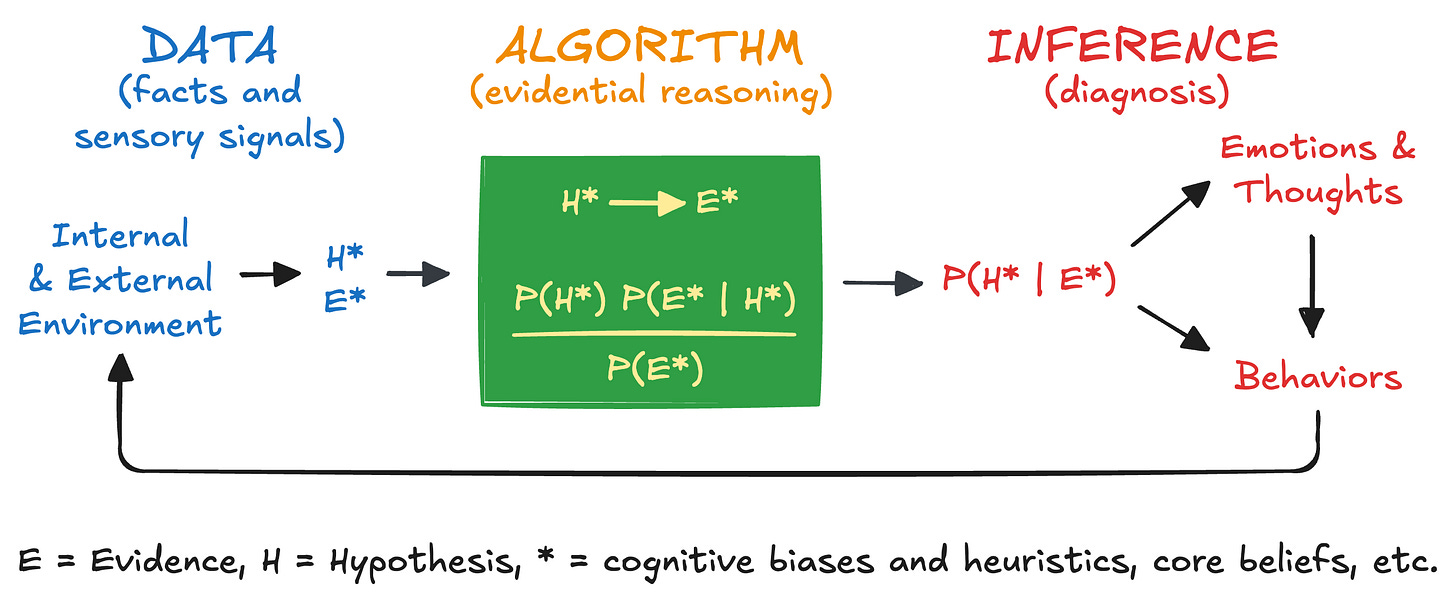

Finally, Bayesian algorithmic thinking (BAT) enables us to generalize more broadly to the everyday processing of data (evidence), evaluating causality (hypothesis), and drawing conclusions (inference).

“BNs have a superpower — they provide a unifying framework for understanding … probabilistic reasoning, causal inference, and decision analysis.”

BAT supercharges your critical thinking, keeps you intellectually humble, and accelerates your learning and improvement. All public health professionals should understand basic BAT.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 depicts BAT as

inputs (data),

processes (algorithms),

outputs (inferences), and

outcomes (emotions, thoughts, decisions, and behaviors).

Figure 2 depicts causal/predictive reasoning with cause-effect nodes

and the conditional probability P(Effect | Cause) which is used for prediction.

In contrast, Figure 3 depicts evidential/diagnostic reasoning and Bayes’ Theorem with the hypothesis-evidence nodes

and the inverse conditional probability P(Hypothesis | Evidence) which is used for diagnosis.

For this posting (Part 2), we focus on Figure 2 — causal/predictive reasoning.

Causal/predictive reasoning — Cognitive biases

From Table 1 we see that the causal/predictive reasoning rows have two probabilities

P(H)or prior probability of HP(E|H)or likelihood (how probable the evidence is if the hypothesis is true)

For concreteness, let’s consider the false claim that vaccines (hypothesis) are causally linked to autism (evidence).34 The prior probability is the P(vaccine exposure in early childhood) or P(V) — the P(hypothesis). The likelihood is P(autism given exposure to vaccines in early childhood) or P(A|V). — the P(evidence|hypothesis).

P(V)=P(A|V)= P(autism | vaccine exposure in early childhood)

Ideally, these probabilities, P(V)and P(A|V), should only come from objective, high quality, scientific studies. However, even when great evidence exists, this is insufficient. Remember, with BAT we consider three entities:

probabilities (eg, risks of adverse events, diagnostic testing),

credibility of a hypothesis (eg, new evidence regarding causal claims), and

beliefs (subjective, personal beliefs).

So, even when strong evidence (probabilities) exists, others may not find it credible because of their beliefs. BAT handles not only probabilities, but also psychological information processing. As humans, we have

core beliefs (eg, medical freedom movement) — data (inputs)

cognitive biases (eg, confirmation bias) — algorithms (processes)

updated beliefs about vaccines and autism — inferences (outputs)

Rather than Bayesian Algorithmic Thinking — the ideal — we instead have “Biased” Algorithmic Thinking. From Oeberst and Imhoff:5

“One of the essential insights from psychological research is that people’s information processing is often biased. … [cognitive] biases (e.g., bias blind spot, hostile media bias, egocentric/ethnocentric bias, outcome bias) can be traced back to the combination of a fundamental prior belief and humans’ tendency toward belief-consistent information processing.” (emphasis added)

These bias-generation algorithms applies to all of us and not just to “anti-vaxxers” or anti-science conspiracy theorists. All of us generate and reinforce cognitive biases:

fundamental prior beliefs — data (inputs)

belief-consistent information processing — algorithms (processes)

generation/reinforcing of cognitive biases — inferences (outputs)

These biases drive reinforcing feedback (causal) loops making non-science-based beliefs strong and stronger. Understanding this is critically important so that we …

empathize with and have compassion for others whose conspiratorial beliefs clash with scientific, evidence-based norms,6

do not judge others whose conspiratorial beliefs clash with scientific, evidence-based norms, and

check and mitigate our cognitive biases.

Oeberst and Imhoff argue that humans have six fundamental prior beliefs (data) that shape belief-consistent information processing (algorithms) resulting in biases (inferences). Here are the six fundamental prior beliefs:

“My experience is a reasonable reference.”

“I make correct assessments of the world.”

“I am good.” (eg, character, competence, caring)

“My group is a reasonable reference.”

“My group (members) is (are) good.” (eg, character, competence, caring)

“People’s attributes (not context) shape outcomes.”

To begin to mitigate your biases, assume these six fundamental beliefs are false with respect to you and your group: “WHAT IF …

…, my experience is NOT a reasonable reference.”

…, I make INCORRECT assessments of the world.”

…, I am NOT good.” (eg, character, competence, caring)

…, my group is NOT a reasonable reference.”

…, my group (members) is (are) NOT good.” (eg, character, competence, caring)

…, people’s attributes (not context) DO NOT shape outcomes.”

Then, with intent and vigor, always

challenge your assumptions

seek objective, verifiable data and evidence

prove yourself wrong — cultivate “disconfirmation bias”

Stay intellectually humble; make hypothesis-evidence your default; then, predict, experiment (or measure), identify and close prediction-error gaps, learn, and improve.

Part 3 preview

For Part 3 we will continue with causal/predictive reasoning with a focus on

Correlation is not causation

Alternative explanations

Confounding (common effect)

Abduction (common causes)

In future posts, I will cover decision analysis, computation, and more than two nodes.

Thanks for supporting TEAM Public Health by reading this blog! Please share.

TEAM Public Health is a FREE — not-for-profit and reader-supported — blog. All content is freely available to all and is designed to be evergreen.

Serving with you,

Footnotes

Scutari, Marco, and Jean-Baptiste Denis. Bayesian Networks: With Examples in R. Second edition. Texts in Statistical Science Series. CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group, 2022.

Fenton, Norman E., and Martin Neil. Risk Assessment and Decision Analysis with Bayesian Networks. Second edition. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, 2019.

Kerry Breen, Michael Kaplan, and Céline Gounder. “CDC Website Is Changed to Include False Claim about Autism and Vaccines.” CBS New HealthWatch, November 22, 2025. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/cdc-website-change-vaccines-autism/.

Céline Gounder. “What the CDC’s Vaccine Language Shift Reveals About Pseudoscience.” Substack. Ask Dr. Gounder, December 20, 2025.

Oeberst, Aileen, and Roland Imhoff. “Toward Parsimony in Bias Research: A Proposed Common Framework of Belief-Consistent Information Processing for a Set of Biases.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 18, no. 6 (2023): 1464–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916221148147.

Leonard, Marie-Jeanne, and Frederick L. Philippe. “Conspiracy Theories: A Public Health Concern and How to Address It.” Frontiers in Psychology 12 (2021): 682931. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.682931.

Strong framing of how algorithmic thinking can sharpen our reasoning but also amplify biases when we're not careful. What clicked for me is that the same structure that helps us process evidence objectively can reinforce belief-consistant pathways if we skip the humility step. I've caught myself doing this when evaluating new research, essentially filtering data through prior assumptions rather than questioning them. The six fundamental beliefs list is practical, it gives you handholds for self-auditing rather than vague advice about stayin open-minded.

This was a thoughtful and engaging piece—thank you for writing it. As an epidemiologist, some of these ideas are relatively new to me, and I’m still learning how to think about the role of subjectivity alongside objectivity. In scientific practice, we’re trained to minimize subjective steps in causal inference and diagnostic reasoning, so I find myself pausing when ethical or moral perspectives are framed through scientific language, particularly around conspiracy beliefs. Without clear boundaries, this can create gray areas that are open to individual interpretation and risk blurring empirical explanation with normative judgment. I appreciate the perspective you’re offering and see real value in the conversation—it’s helped me reflect more carefully on where explanation, interpretation, and evaluation intersect.

I’d be curious to hear how you distinguish, in your framework, between empirical explanation and normative or ethical evaluation.